What Game Theory Teaches Us About Justice

How a computer engineering tournament might have taught society how to deal with criminals and murderers.

Hey Astros,

This is the next part in the “Deadly Dilemmas” series. If you’re not caught up, go read the first two parts in the series. It won’t take long, which is the point. All my pieces from now on are designed to be shorter and more condensed.

Also, I’m going to begin adding word counts to each piece and estimated reading times. Hopefully, it’ll help keep you engaged, because I know the writing won’t…

Just kidding, I know I’m a great writer.

Enjoy!

Words: 1473

Estimated Reading Time: 5-6 Minutes

Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948) stated that “An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind.” I tend to agree with this statement. However, as I sit here at this coffee shop considering the statement, I find myself deeply conflicted. If you steal from me, can I really just sit back and take it? If people who tend towards thievery find out that I let people steal from me without consequence, what happens next? Obviously, I will probably get robbed far more often. But, according to Gandhi, if we keep repeatedly stealing from each other just because we stole from each other in the past, we will all end up with nothing.

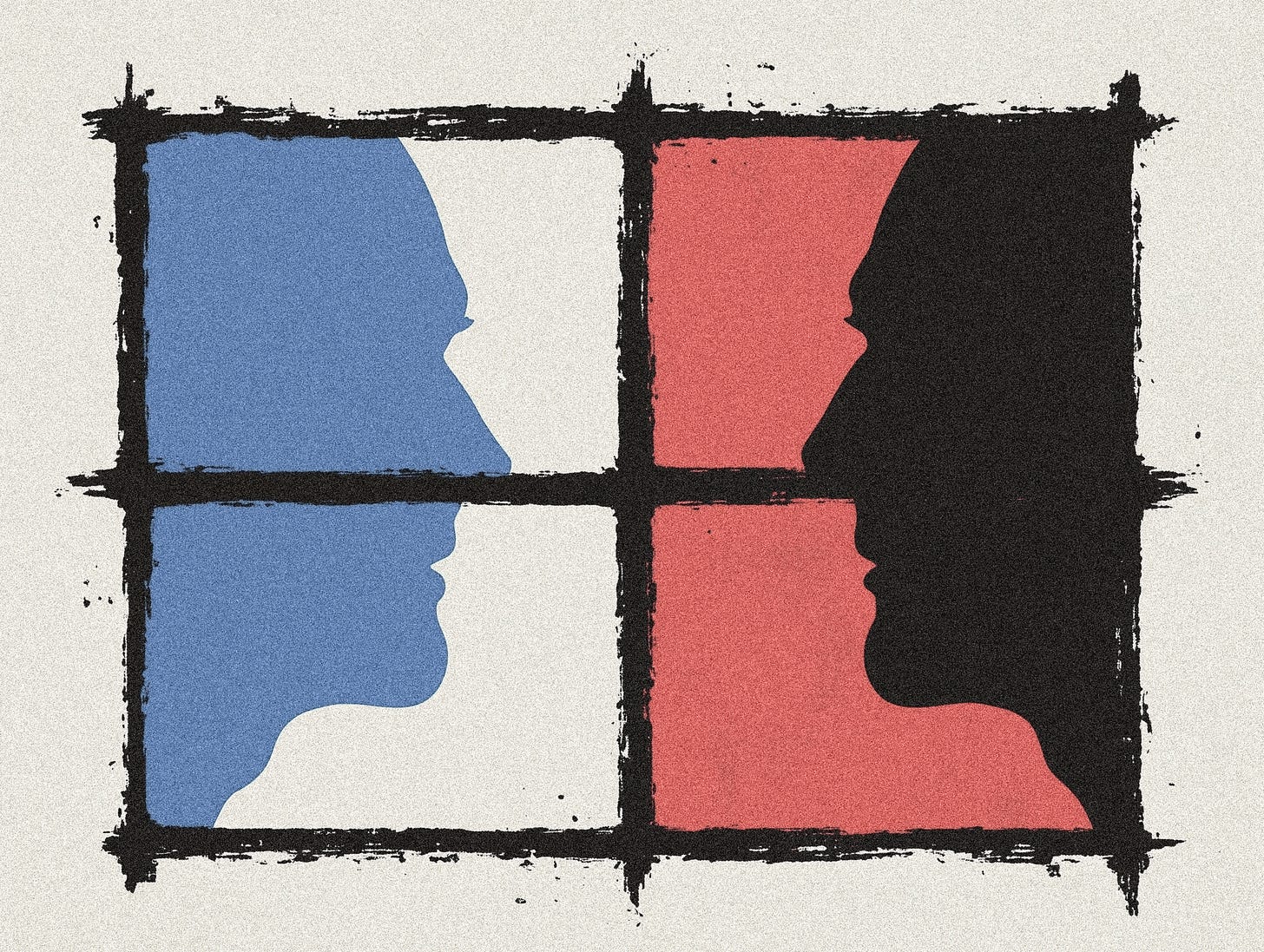

Society deeply fears falling into constant thievery and murder so much that it rejects Gandhi’s second half of his statement and just keeps the first. That’s why, in many states in America, there is the death penalty. But is this really the most effective strategy for creating a peaceful society? Or is it just mutually assured destruction?

I don’t think Gandhi is entirely right. But I don’t think society is entirely right either.

My solution for a peaceful society is embedded within the solution for a concept called Prisoner’s Dilemma. Prisoner’s Dilemma offers us insight into mutual decision making and consequences, the exact type of decision making and consequence structure that gives us the phrase “an eye for an eye”.

Prisoner’s Dilemma is a game theory concept in which there are two suspects arrested and brought into the police station for questioning over a crime. The investigator asks each of the suspects who committed the crime. Based on the outcome of both parties’ decisions, each prisoner receives a prison sentence. But the length of the sentence varies based on whether they confess or defect and rat out their counterpart. Here’s how it works…

Our suspects, Prisoner A and Prisoner B, are trying to get the shortest sentence possible for a crime they both committed. They can either confess to their crime or defect and blame it on the other. If they both choose to confess, each suspect receives one year in prison. If Prisoner A chooses to defect and blame it on their counterpart while Prisoner B chooses to confess, Prisoner A gets zero years while Prisoner B gets three years in prison. If both Prisoner A and Prisoner B decide to defect and blame it on each other, they each get two years in prison.

However, there’s a twist. Neither suspect knows what the other is going to do. They must hope that their counterpart makes a choice that maximally benefits themselves. The obvious choice is to defect. Because you either get zero years in prison or a maximum of two. If you confess, you’re going to jail for a while no matter what.

This example is called a One-Shot Game of Prisoner’s Dilemma. It actually emulates many of life’s decisions. We can cooperate with other people for a smaller but mutual benefit. Or we can screw over our counterpart for maximal benefit to ourselves. You’ve probably been in positions in life, either in business or your personal life, where you had one of these choices. Think of drafting a contract for a business partnership, deciding whether to offer a friend help, etc.

But the problem is, life is never just a one-shot game. Life is a series of games of Prisoner’s Dilemma, called Iterative Prisoner’s Dilemma. This is where the person we are interacting with knows of our past actions, and our past actions will influence how people will treat us in the future. If you cooperate with others, they’ll be more likely to cooperate with you next time. But if you screw people over, they are less likely to work with you in the future. Or they’ll screw you over if given the chance.

In the 1980s, a man named Robert Axelrod held a series of computer tournaments in which computer engineers were tasked to come up with a strategy to win a game of Iterative Prisoner’s Dilemma. They would put two strategies up against each other head-to-head to see which strategy would win. Instead of prison sentences, the outcome of each round provided each strategy with “points”.

Some people would come up with mean strategies. These mean strategies would default to defection very easily. That means they would either start with defection or always defect. Or, like Grim Trigger, would defect every time after their opponent defected once. Other strategies, like Tester, would start cooperating, but then defect occasionally to see how nice the other strategy was. Nicer strategies got taken advantage of, continuing to cooperate despite Tester defecting, and as a result giving Tester far more points in the process (remind you of any of your friends (or enemies)?).

Other strategies, like Tit for Tat, were designed to be nicer strategies. These strategies defaulted to cooperation. One strategy, called “Always Cooperate,” literally just always cooperated, no matter the cruelness of its opponents past actions (we all probably know someone like this). These nice strategies, on average, scored higher than meaner strategies.

Although we learned that defecting works better when two people only play one game of Prisoner’s Dilemma, when you play many games back-to-back and understand the other sides tendencies, cooperating actually scores better.

The winningest strategy, Tit for Tat, defaulted to cooperating. And then reacted based on what their opponent did in the past round. If in the previous round their opponent cooperated, in the next round, Tit for Tat would cooperate. If the opponent defected, Tit for Tat would defect in the next round. However, if the defector returned to cooperating, Tit for Tat would return to cooperating as well.

Basically, Tit for Tat started by being nice to maximize the number of points for each. However, it proved in its behavior that it will not be taken advantage of. If their opponent defected, it would respond by defecting. Put two Tit for Tat strategies up against each other, and they will go on forever cooperating and getting two points each time they do so, assuring consistent mutual gain (you hopefully have at least one relationship in your life that is like this).

Another important thing to realize about Tit for Tat’s success is that not only would it not be taken advantage of. But it was capable of forgiveness. If its opponent defected but then returned to cooperating, it would also return to cooperation.

The success of Tit for Tat and the nicer strategies in Axelrod’s tournaments prove a key component of life: nice guys finish first in the long run. There are a million stories of people screwing people over, winning for a little while, but then losing their reputation and freedom (or even life) for it. Take Bernie Madoff, Harvey Weinstein, Elizabeth Holmes, and others. In the end, society cast them out by putting them in jail or ostracizing them or killing them.

And on the flip side, we are constantly reminded that being a good person, who doesn’t allow themselves to be taken advantage of, will be rewarded handsomely by society. Billionaire company founders who got investors to invest in their second company because they made them so much money the first time. Jimmy Donaldson, who got $100 million to create Beast Games on Amazon because he has built such a massive following and positive reputation for himself on YouTube. Even things as small as a local restaurant donating to a food pantry might be rewarded with more new customers by a local news station running a story about their good deed.

I think the study of game theory and the success of Tit for Tat so perfectly maps to the real-world that we must consider it as a guide for operating in life. Because I find it so essential, here again are our lessons from Tit for Tat:

· Begin each relationship by cooperating.

· Do not let others take advantage of you when they do not cooperate.

· Forgive others for defecting.

Tit for Tat does not promote “an eye for an eye”. Tit for Tat operates in a world in which there is always room to forgive. There is no forgiveness with the death penalty. Once you kill someone who has previously killed others, you can’t give them a chance for redemption. Which, I think you should.

But Gandhi’s claim that if we blind others for blinding us then the whole world would be burdened by blindness, leaves kind individuals vulnerable to exploitation. And leaves the worst of society to get off without consequence, incentivizing bad behavior.

So, where’s the middle ground? How, in the context of the death penalty, can we apply Tit for Tat’s fair but firm style to upgrade what we do with society’s worst offenders? Or should we even care at all and just kill killers?

Part 4 answering those finals questions coming soon…

Read Next: Create a Life Mission Statement

I Hope you enjoyed that piece! I know I know, I’ve been a little dark lately. Honestly, expect it to continue. I’m literally trying to figure out when it’s okay for society to decide on the death of others. I’m doing the Lord’s work here, cut me some slack.

But I want you to know, I’m a very happy guy. I’m actually very optimistic, really! You’d be amazed. My life is awesome. And I hope yours is awesome too.

Go introduce yourself in the comment section and I’ll tell you my favorite Reese’s product.