The Two-Marshmallow Mindset

How to Rewire Your Brain for Long-Term Success

I want to start this piece with a disclaimer. I’m not financially successful. Nor am I successful in most of the ways people typically associate with the word. This being the case, I thought this would be a good opportunity to briefly discuss why I write.

I write to clarify what I’m unsure about, or to test ideas I think I’ve solved to see if they hold up. People might use conversation, brainstorming, or long walks. I use my keyboard.

I hope this disclaimer helps you identify the reason I’m writing this piece. It’s not to teach you. Although, if you find it valuable and educational then all power to you. It’s to teach myself. And to solidify ideas I have had circulating in my mind for about six years.

Humans Aren’t Wired for Long-Term Thinking

Alex sat there with the nice man in the lab coat. Alex looked around the room. The room had all white walls. There was a big mirror in front of him. Beside the big mirror, a wooden door. The man in the lab coat sat across from him. He reached into his coat pocket and revealed a marshmallow. He placed the marshmallow in front of Alex. Alex reached out to grab it.

“No no, Alex, you can’t have that right now,” the nice man said. “Now, I’m going to leave this room. And you’re going to sit right here. When I come back, if you still haven’t eaten that marshmallow, I’ll give you two. How does that sound?”

“Okay,” Alex replied.

The man left the room through the door next to the giant mirror. Alex sat there. He kept shifting in his seat. The marshmallow in front of him seemed to beg for his attention. But he wanted two marshmallows. So, he sat on his hands and waited.

The researcher never returned. Minutes ticked by. At least, he thought they had. There was no clock in the room. And he couldn’t read the clock anyway even if there was one in the room. His new position became uncomfortable. He removed his hands from under his butt, which had begun to tingle. He placed his hands on the table. The hands gravitated towards the marshmallow. He put his hands around the marshmallow. He picked it up. He played with it in his hands.

The nice man wasn’t in the room. Alex believed that he would never see what would happen next.

Alex ate the marshmallow.

The researcher returned soon after, empty-handed. He patted Alex on the head while Alex, mouth still full of his only marshmallow, followed him out of the room.

You’ve probably heard a version of this story before. The “Marshmallow Test” was originally done in 1970 by researcher Walter Mishel. He created this study to attempt to prove a hypothesis. That one’s ability to delay gratification improves one's chances of having success in life. That long-term thinking is the better approach to finding success in modern life.

The test was simple and easy to execute. If the child cannot wait for the second marshmallow, they have a poor ability to delay gratification. And if they can wait for the second marshmallow, then they have a good ability to delay gratification. After determining the child’s ability, he tracked their life trajectory to determine if their ability to delay gratification resulted in greater life outcomes. He concluded that, yes, if a child waits to get more marshmallows, then they will be more successful later in life (based on specific criteria). But future studies to replicate the results were mixed.

However, just because this study didn’t achieve a repeatable result doesn’t mean that being able to delay gratification doesn’t result in more success in life. It just may mean that the Marshmallow Test is a bad judge of this characteristic. I think that Mishel’s hypothesis remains a good one. Long-term thinking, as I see it anecdotally around me, results in incredible returns for those who can do it. Because modern society isn’t built like the one we evolved in. And success today doesn’t mean what it did thousands of years ago.

Thousands of years ago, humans were a survival species. We spent our time in the wild just trying to make it to the next day. We lived in small clans. There was no larger society with norms and governments and jobs and HR departments and stock markets. Humans of the survival era didn’t need to know what a compound interest curve or an equity was. They needed to know where the lions made their kill so they could scavenge the scraps. Then, after they had learned to develop weapons, they needed to know where the herd was moving so they could pick off a weak link. All their decisions had immediate returns or consequences. The long-term was irrelevant. Maybe reputation mattered a bit. But not like it does today.

Only for a brief period of human existence have the long-term consequences of our actions really mattered. As a result of this evolutionary pressure, we became wired for short-term thinking. We are wired for instant gratification. We are wired to eat the one marshmallow right now before the nice man in the white coat comes back in the room with another.

But there are the rare few of us who can fight that deeply encoded, short-term thinking nature. And we can learn a lot from the way they see the modern world.

There are Those That See the Future

As a business owner myself, I deeply admire other business owners and entrepreneurs. Guys like Musk, Bezos, and Jobs are on the list of people I take notes from. Another class of people I admire are investors. Stan Druckenmiller, Peter Thiel, Bill Ackman, and Charlie Munger are incredibly interesting to me. And I’m constantly seeking out their guidance (thanks Lex Fridman for sharing).

One of the things I like about investors is their ability to see long-term. Stanley Druckenmiller, one of the greatest living investors we have today, said this about investing:

“It doesn’t matter what a company’s earning, what they have earned – you have to visualize the situation 18 months from now – that’s where the price will be.”

Investors like Druckenmiller, Buffett, and Ackman might be categorized as value investors. Ackman’s firm, Pershing Square Capital, owns only 8 to 12 assets at a time. And when they buy, they buy to own, not to trade. ‘Trading’ in the stock market means flipping an equity over a short period of time, as in a few months or even days. Don’t get me wrong, some stock traders do well. They might do financially better than some top-flight doctors or lawyers if they’re really good. But all the billionaire investors whose names people know don’t trade stocks. They invest in their assets for years and often decades.

For making vast sums of money, the best investors in the world continually prove that the long-term matters a lot. But it’s not just investing where the long-term matters. An executive who has stayed in the same industry for decades usually makes far more in salary than a person hopping from job to job in different sectors. A business owner who operates the same business, making little improvements all the time, usually has a far larger business after twenty years than an entrepreneur constantly starting up and winding down businesses in different sectors when the previous business doesn’t grow as fast as they would like.

But why is that? Why, does it seem to me, that waiting for two marshmallows is better than eating the first marshmallow you are given? Isn’t a bird in the hand worth two in the bush?

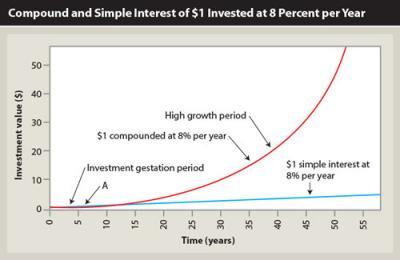

Actually, no. The two birds in the bush are worth far more than the one in your hand. Exponentially more. And the reason why is because of compound interest.

Compound interest is the idea that when you reinvest interest earned into an appreciating asset, the value of the interest earned grows exponentially, because it is calculated by the new, larger sum upon each reinvestment period. You might need to read that again, but I’ll provide you with some real-world examples below to help.

Think about Alex, the young boy who couldn’t stop himself from eating that marshmallow. Let’s say Alex was more patient and was able to not eat the marshmallow in front of him. And let’s say that the lab coat man had come back every 5-minutes with a new offer. Instead of just giving Alex another marshmallow, the lab coat man tells Alex that if Alex does not eat any of the marshmallows that he currently has, the lab coat man will double the number of marshmallows that he will give Alex. Meaning, if Alex has two marshmallows on the table and doesn’t eat them, five minutes later he will get two more.

Now, answer this: how long will it take for Alex to have enough marshmallows for the rest of his life and still have some left over for his entire extended family?

Well, within 1 hour and 40 minutes he will have 1 million marshmallows. Yes, you heard that right, 1 million marshmallows. That’s how powerful the compound interest curve can be.

Now, getting a million of anything in less than two hours seems unrealistic. Maybe a game show might provide you with such an opportunity (if it’s produced by MrBeast), but not real life. But the compound interest curve absolutely exists in real life. It just happens slower.

To demonstrate what compounding might look like in real life, let’s consider a fictitious small business and their fictional revenue. There’s a new burger joint in town owned by Sam called “Sam’s Burger Shack” (yes, I’m equally as creative as the authors of your fifth-grade math textbook, thank you very much). If Sam’s Burger Shack makes $100,000 in revenue in year one and the revenue grows 20% each year for five years, how much will their revenue be in year five?

You might think it will be $200,000. Because 20% of $100,000 is $20,000. Multiply $20,000 by five and you get $100,000. Add that to the original revenue of $100,000 and bam, $200,000.

But no, that’s not the way the world works. If a business is growing 20% every year, it’s not growing 20% from its original value. It’s growing 20% from its new value, which is 20% higher than the previous year.

So, let’s run the numbers for Sam’s Burger Shack with this better understanding. If in year two the revenue was $120,000 and it grew another 20%, you would multiply $120,000 by 0.2 to know the revenue increase, which would end up being $24,000 in new revenue. Then, you would add this value to the $120,000 in total revenue. So, year three revenue is actually $144,000, not $140,000.

By year five, Sam is doing alright. His revenue is now $207,360. That’s over double from year one and also $7,360 more dollars than our previous, broken calculation where we just added $20,000 each time.

Now, as I said, compound interest in real life happens far slower than it did for Alex, who was getting millions of marshmallows in only two hours’ time. After 5 years of hard work and with an extra $7,360 in his pocket, Sam doesn’t really feel that his business is on an exponential trajectory to the moon. To be honest, the $7,360 could just have been a rounding error.

But after year 5, the curve will get crazier.

And at year 10, if he just keeps growing at 20%, he will be making $515,978.04 in yearly revenue. If we didn’t take into account compound interest and we only added $20,000 each year, he would have been only making $300,000.

But Sam isn’t a quitter. He is dedicated to the Burger Shacks that bear his name. He’s not done by year 10. He keeps pushing so that his business continues to grow by 20% every year. By year 15, Sam is bringing home $1,283,918.46 in revenue.

That number might seem insane to you. That’s because it kind of is. If Sam opened his first Burger Shack at twenty-five, that means he is making millions at only age 40. How can Sam be a millionaire in such a short period of time while most people are still struggling to bring home $150,000 in their corporate hellhole jobs while begging for a 5% pay raise each year?

Comparison is the Thief of Reason

Me comparing myself at twenty-eight, only three years into my small business, with someone like Sam, who is forty, and is five times further ahead than me, highlights another problem with the way humans are wired. Not only are we wired for short-term thinking, but we also have terrible time perception. We can’t empathize on long time horizons. One of the problems with hearing other people’s stories of success is that they’ll tell you about all of their trials and tribulations in a two-hour podcast. And if two hours seems like a long time to hear the suffering a human went through to experience success, Hollywood will solve that for you by cramming the hardest parts of a character’s life into a two-minute montage before showing the protagonist enjoying a penthouse view of NYC.

Let’s go back to our friend Sam. Of course, Sam is a fictional character created by my imagination. But let’s pretend he is real. Because, let’s be honest, the story of Sam has played out countless times in companies such as McDonald’s, Five Guys, and Wendy’s.

If I tell you, “Sam make $1.2 milly at only age forty,” you’re not getting the whole picture of Sam’s suffering. You’re not watching Sam toil away in his Burger Shack for years before he could take a dollar out of it to pay himself. You’re not watching him deal with employee headaches, landlords, and the imbecile contractor who keeps delaying the buildout on his fourth location. You weren’t there when the health inspector, who is a lifetime friend with Ronny of Ronny’s Burger Palace, gave him a ‘C’ rating and forced him to close the doors of his Central Ave location for a month in June, which is his (and Ronny’s) busiest month of the year. And Sam still closed that year up 20%. What a resilient fucker. Take that, Ronny.

Sam earned all his $1.2 milly in revenue through blood, sweat, and tears. The full gravity of which will never come across in a two-hour podcast or a two-minute montage in a movie about his life.

Unfortunately, as I said, many people don’t appreciate how much suffering they need to go through to experience compound interest. It’ll take years. Decades, even. And if you cut off the compounding before it has a chance to go exponential, you’re going to miss out on all the good stuff.

To Take Advantage of the Compound Curve, You Must Think Long-Term

Let’s say Sam decided to shut down his Burger Shack in year five. At the time, the compound interest curve was hardly kicking in. At $7,360 extra dollars, Sam might not have even realized there was growing inertia building underneath him that would take him miles further if he just kept at it. Instead of riding this wave that would build exponentially over time, Sam shut down the Burger Shack. He moved to a new town, with new people, to start a landscaping business. He did this because his friend in his old town, who had a landscaping business for fifteen years, was making over a million a year (about $1.2 milly, to be exact). Sam, at the time, was hardly making two hundred. Clearly, the money is in lawncare, not burgers.

We now know that, based on everything I said earlier (that I’m obviously right about, by the way), that Sam shutting down his Burger Shack would be a mistake. But we also know that not everyone owns a business. My fictional case study doesn’t apply to everyone. Or, at least, won’t resonate with everyone. Because here’s the thing, everyone should invest their money earned from their corporate hellhole job, if that’s what they have. And compound interest applies here too (duh, John, I’m not a fucking idiot).

And the reason people don’t make money investing (or, at least, not as much money as they could), is because they cut off the compound interest curve before it is able to take effect. Just like Sam could have if he ended his Burger Shack business to do landscaping.

Okay, what I’m going to say next is going to sound really naïve (and probably dumb because I don’t have any money in the stock market), but I asked a lot of my clients who are in finance about this and they agreed with me (and consensus is truth, as I’ve said before and will say again (trust the experts (especially if they’re endorsed by CNN)/believe in science (I’m being sarcastic, in case you couldn’t tell))).

Anyway, here it goes…

I realized recently that most investment decisions are easy to make. Your goal in investing is to make money. You don’t want to lose money. So, you want to give yourself the best possible chance of making money while also not losing money (goddamnit John get to the point already).

Many people, as I said earlier, do stock trading. They buy some equity or asset in the stock market, wait a few hours, days, or months, and then flip it for a profit based on a news story or hype cycle. You can follow their lead and trade on hype cycles and the news. “Oh, Elon is going to be running a shadow organization for Trump, better buy Tesla stock!” Or you can take Stan Druckenmiller’s advice and think about what the price will be 18 months from now. If you have a company that is doing well and has a competitive advantage, it’ll probably be easier to guess if it’ll be worth more than it is today in a year and a half compared to knowing how it’ll fluctuate on a daily basis.

But my guess is that your decision gets easier the longer you look out into the future. And I mean much longer into the future.

Let’s go to the future by first looking at the past. Let’s travel back to 2005. One of the top five companies in Dow Jones at the time was Microsoft. It was valued at the time at around $280 billion. Now, at the time, you could pretty confidently say that the computer and software industry was growing fast with no end in sight. If you looked at the future, you could reasonably predict that computers were going to be a bigger and bigger part of our lives. Within twenty years, you could guess that the computer industry would be larger than it is in 2005. You didn’t have to look at any spreadsheets to make this claim. You didn’t have to be a Wall Street insider. You just had to own a Windows computer and browse the relatively new thing called “the internet” occasionally to see this as an inevitability.

Placing a bet on Microsoft should have seemed like a no-brainer at the time. They were a super-dominant player in a quickly growing market. And if you placed that bet, you would have been right. As Microsoft is now valued at $3.11 trillion as of this writing (January 11, 2025).

Now, let’s say you invested $10,000 in 2005. Today, it would be worth $227,800. That’s without reinvesting dividend payments. Which, as we have seen with the compound interest curve, can dramatically increase earnings.

Now, hindsight is 20/20, of course. You’re probably all like “Yeah, John, and if I bought Bitcoin when it was first created, I would be able to buy Greenland before Trump does.”

That’s a fair criticism. And I agree with it. So, let me make a future prediction that I think very few people would disagree with based on the same principles.

Right now, the battery electric vehicle (BEV) market is growing at a compound annual growth rate of around 20%. Just like Sam’s Burger Shack’s revenue. That means, in a few years, exponentially more electric cars will be on the road. It’s also easy to imagine a world where everyone has a battery electric car. We can predict with a high degree of certainty that BEV’s will be the dominant mode of transportation for people in the future. Just like it was easy in 2005 to imagine every person owning a computer (or several).

You don’t even have to know the compound growth rate of the battery electric car market to understand and see this trend. Everywhere you look you’re probably thinking: These goddamn electric cars are everywhere!

In my opinion, that thought in your mind is probably enough data to make a bet on a company in the BEV market to be worth more 20 years from now than it is today and buy their stock.

And then, from there, it’s not hard to choose a company. We also see full self-driving cars finally being a real thing. Waymo has full self-driving taxis in San Francisco today. Tesla has had full self-drive packages for its cars for multiple years. And we can all easily imagine a future with cars that drive themselves. It’s probably an inevitability, just like computers were.

Combine those two markets, battery electric cars and self-driving, and you have one company: Tesla. Tesla currently owns about 15-20% of the entire global BEV market. And they have the only full self-driving functionality in a consumer car (well, the only one that is any good).

Right now, Tesla is up just a little bit, sitting at a market cap of $1.27 trillion as of this writing, since it went public in 2010 at a market cap of $2.88 billion.

And upon reading that you might be thinking “John, how much more can Tesla possibly be worth! It’s already worth so much and it started at so little!!!!!”

But this is the primary mistake people make in investing. They think that the upside is limited. When really, the upside is unlimited.

My point is that you shouldn’t fear where the price of something is today versus its historical price when trying to make an investing decision. The past is the past. The future is what you’re investing in. Take your emotions and pessimism out of the equation.

Tesla will, most likely, be worth a lot more 20 years from now. Will it be worth more in six months from now? I don’t know. And I don’t care. What happens six months from now doesn’t matter. That’s short-term. If you stop thinking about the short-term, it’s very easy to make an investing decision.

Long-term thinking can solve your money problems. It’ll increase your short-term suffering, sure. You’ll have to suffer at your corporate hellhole job. But those 5% pay raises will compound. You’ll have to stick it out with your small business that feels constantly on the precipice of collapse, but that 20% revenue growth will compound. And long-term, you’ll end up like my clients. You’ll live in a vacation town and then take vacations to even nicer places on planes that only take you and your family to resorts that bring you a fruity cocktail every hour without you having to raise a hand to ask for a refill.

Read Next: Why Men Should Learn to Dance

You Up?

I’m not asking for a booty call at 2am, I promise (unless you’re down?).

I’m simply asking you to talk to me. You see, I’m lonely and in need of friends. Ideally smart ones (like you, which I can tell is the case since you made it this far reading my work which is expressly designed for high IQ smarty pants like you and I).

Leave a comment below so we can chat. And please make it about something you want to talk about in this blog. I’m not trying to get to know you. I just want your intellectually robust comments so that future readers will be inspired to also leave comments and exponentially propel my future fame and success.

Is that too much to ask?

I think that also the Battery Market is going to blow, investing in companies like ESS or Ambri is going to be great.