Stop Buying Your Cheeseburger on Credit

Part 2 of me telling you why everything is so gosh dang expensive.

Words: 1663

Reading Time: 6.5-8 Minutes

Why Does Everyone Have the New iPhone?

When I was eighteen, I worked in a pizza restaurant. I was a delivery driver. It was a fantastic job. The pay was decent (more than $15/hour eleven years ago), and the work was easy. I liked to drive, and I liked listening to music (still do, though driving not so much). It was the perfect job.

I had this coworker, his name was also John, who always complained about money. His parents were poor (or principled, maybe), and they made him pay for everything, including his car and his phone.

One day, he showed up to work with the newest iPhone. After all his complaining about how broke he was, I had to ask.

“Is that the new iPhone?” I asked him.

“Yeah man, it’s pretty sweet,” John replied.

“Isn’t that thing like $900? I thought you said you were broke.”

“Yeah, but dude I didn’t pay for it up front. Nobody does that. It’s only like thirty-something a month. And they gave me a good deal on my trade in.”

John was right, hardly anyone paid for their phone up front back then. And few people do today.

Telecom companies like Verizon and AT&T have had a strangle-hold on phone markets for a long time. And they have all come to this clever agreement with their customers. They convince their customers that if they just sign a long-term contract, wherein they pay monthly for their phone instead of up front, they can pay zero-interest for the whole term.

The common term duration used to be 24 months. But now that people want new phones less often, as phone technology fails to improve dramatically over time, the loan terms are now 36 months. They’ll even give you massive credit for your old, beat-up phone, for signing on the dotted line. With favorable loan durations and excellent trade-in incentives, you can be paying as low as $8 or $10 a month for the newest iPhone, which retails for $1,200-$2,000.

As a result of these contracts, the barrier to getting the “latest and greatest” tech is low. Most people, no matter how poor, can afford $10 a month. Now, it feels like everyone has the newest iPhone, no matter how much money they have. However, as you can imagine, these contracts aren’t as good as they seem.

Nothing is, unfortunately.

These contracts are actually a scam. If you bought a phone through a carrier with trade-in credits (as most do) and then decide to pay off your phone early and leave your carrier, you must then pay the full price of the phone, minus whatever small payments you have made over the months you have been paying. The credits for that phone you gave them go away. You never get your old phone back. That phone belonged to your carrier the moment you signed it over.

These telecom companies make the process of paying off your phone as painful as possible to keep you from leaving. And with the prices of phones being so high, most people who can afford an $8-a-month payment probably can’t afford the $743 it’ll take to pay the phone off. They’re trapped.

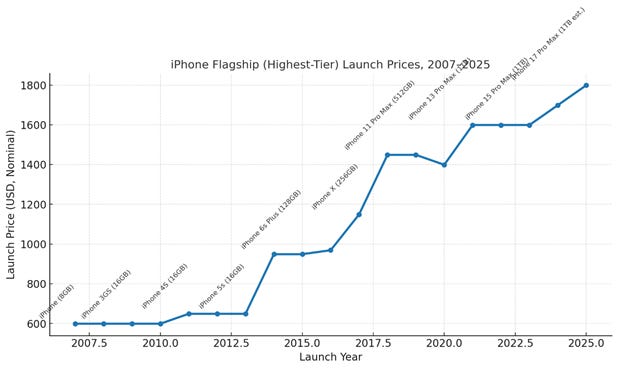

Furthermore, if you look at the prices of iPhones over the past 18 years since the first iPhone was launched, you’ll realize that having everyone pay for their phones on credit has another consequence.

We all know that the iPhone has not gotten much better over the past five years. If I gave you an iPhone from 2020 and asked you to use it instead of whichever phone you have now, you probably would hardly notice the difference.

How has the price of these iPhones continued to climb, despite a lack of the rise in quality? The newest iPhone is now $1,999 for the highest tier. That’s an almost 4x increase over the original iPhone, which was $599 at launch.

Now, you might counter-argue with the fact that inflation has risen a lot since the first iPhone was released. That would be a good counterargument. However, it misses something crucial about technology.

Phone technology has become a commodity. The commoditization of technology should decrease that technology’s price of replication over time. Especially when competing manufacturers make phones as good as the iPhone for one-half to one-third of the price.

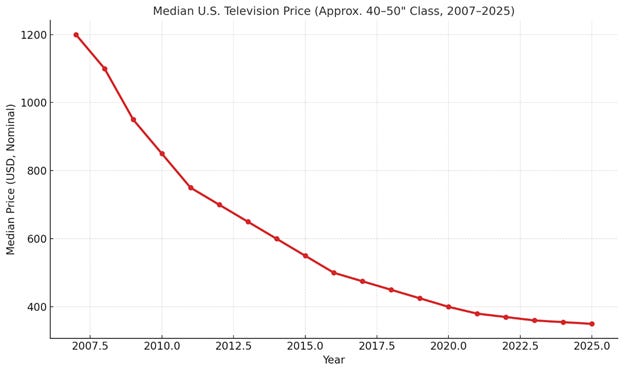

We see this in the television industry. Here is a chart of the median price of televisions from 2007, the year of the launch of the iPhone, to today. This chart includes inflation.

Television technology has increased at arguably the same rate as cell phone technology. The prevalence of OLED displays, shrinking bezel sizes, the thinning of television bodies, the incorporation of computer chips, and the improvement of those computer chips proves that. However, the median price of televisions today is now one-quarter of what it was in 2007. That is almost the exact inverse trend of what we have seen in the cell phone industry.

How could that be?

I’ll tell you how: almost nobody buys their TV with monthly installment plans.

However, people do something even worse with TVs: they buy them with credit cards.

BankAmericard

Credit cards have existed in their modern form—with credit carrying and interest payments—since 1958. They began when Bank of America created a new, revolving credit card concept and called it BankAmericard. They sent these cards to 60,000 residents of Fresno, California.

These were not the credit card applications you get in the mail. These were working credit cards with a $300 limit (~$4,000 today) that one day just appeared on people’s front doorstep. The goal, for Bank of America, was to make money. However, at the time, they also considered it as a sort of social experiment. They really were not sure what would happen.

As you can imagine, the experiment didn’t go well. People went on spending sprees. There were massive delinquency rates. Cards were stolen and lost. Fraud was committed. And millions of dollars were lost.

Fortunately, the credit card was never again used in modern society.

Haha—just kidding, obviously. The execs at Bank of America learned something important: people really wanted to use these credit cards. And so, they came up with an application process, set up some safety rails, and away we went into the Era of Credit.

Years later, BankAmericard was turned into Visa. Then MasterCard, American Express, and Discover entered the industry. Now, in the U.S. alone, Americans hold about $1.2 trillion of credit-card debt.

But credit cards aren’t installment plans like loans. We haven’t created a structured monthly-payment plan system for cheeseburgers.

Or have we?

Cheeseburgers on Layaway

The idea of buying a cheeseburger on layaway seems like a ridiculous idea. At least, it did back in 1997, the year when the movie Good Will Hunting came out. They made a whole scene about it.

If you remember the scene, Will, Chuckie, Morgan, and Billie are driving in the car, having just gotten burgers at a drive-through. Chuckie, played by young Ben Affleck, begins handing out the burgers to his buddies in the car. Morgan, played by Ben’s brother Casey, bought a snow cone before and only had sixteen cents to his name. After irritating Chuckie with his impatience, Chuckie gets fed up and comes up with a plan for Morgan to get his sandwich.

“Alright, well give me yoah fuckin’ sixteen cents that you got on you now and we’ll put yoah fuckin’ sandwich on layaway,” Chuckie says in his thick Boston accent as he puts Morgan’s double burger on the dashboard of his old sedan. “We’ll keep it right up here for you and we’ll put you on a program. Every day you come in with yoah six cents and at the end of the week you get yoah sandwich.”

After his tirade, he ends up throwing the burger to Morgan in the backseat anyway.

These young men, who were poor as the day was long, couldn’t actually imagine buying a burger with installments. They were one step up from getting payday loans to pay their rent. Will worked as a janitor at MIT and Chuckie worked laying brick. But even to these guys, a burger on layaway was hilarious. And at the end of it, Chuckie still had the money to buy his buddy a burger.

But, today, a double burger on layaway is a reality.

Just this year it was announced that you can purchase your DoorDash with Klarna. Klarna is one of the largest buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) corporations. If you don’t know what BNPL is, think “glorified, tech-driven payday loans.” BNPL has digitized the ability for people to pay later for things they cannot afford today.

Klarna has two pay-in-the-future options for your cheeseburger. You can pay for it within a 30-day period. Or you can pay for it with four 0%-interest installments. But, of course, there’s a catch: if you miss a payment, you’ll be charged 20%-36% interest for that double burger that you bought a month ago.

Klarna is not just integrated into DoorDash. It’s everywhere. It’s becoming increasingly popular on more merchant websites. It’s available at grocery stores. And if it’s not Klarna, it’s one of its competitors like Affirm or Afterpay. There’s even an app called Flex that lets people pay their rent with credit.

People are making everything financeable.

This might seem like a good idea. It gives people the opportunity to buy something they might need in a pinch. But I sense a massive issue is coming if we don’t start to think critically about whether we accept these new forms of credit lending.

We have seen people buying now and paying later for homes, cars, and phones for a long time. I never even mentioned student loans, which we could add to that list. And over the course of time, we have seen all these things increase in cost.

If we can finance everything, will there be anything left that stays cheap?

Hey You!

I hope you enjoyed this little two-part series. Now, go be a good little sheep and order DoorDash, buy it on credit, and stay inside before anyone catches you causing a ruckus, talking about ‘Hey, you know, I wish our government wasn’t in so much debt,’ and ‘Why does it seem like the stock market goes up irrationally high when the fed lowers the rates?’

Stop asking questions, little one. You’re not in control of this ship anymore.

Love,

John

The progression from BankAmericard to American Express entering the market shows how quickly credit became normalized as a lifestyle rather than an emergency tool. These companies perfected the art of making debt feel sophisticaed and aspirational, especially AXP with their premium card positioning. The fact that we now have Klarna for DoorDash proves the slippery slope was real all along. When every transaction can be financed, nothing retains its true cost signal and price discovery becomes impossible.