Morality Without Myths

How to get a universal moral compass without the dogmatism of religion. (How to Replace Religion Part 2)

Where does morality come from? As an atheist (or agnostic or whatever you want to label me as), I’ve battled this question forever. It appears to me, as a person who has not murdered nor stole but also doesn’t believe in God, that morality is intrinsic. I see people, religious or not, do good things unto others all the time. Their urge to do good seems to come from within.

For others, however, the answer is extrinsic. Morality is provided to them by their religion. For Christians, Jesus was this miraculous son of Christ who lived a certain way. And if they live life as close to the way he did, then they will be moral. Avoid sin, which is anything that you wouldn’t catch Jesus doing, and they’ll be good. But avoiding sin is almost impossible. So, if they can’t entirely avoid sin, they can just ask for forgiveness when they do sin. And Jesus will forgive them (because forgiveness is one of his virtues) and they’ll still make it to the pearly gates. Easy peasy.

If it’s not intrinsic, is religion the best way to get your morality? My fear with religion as a moral compass is that it can easily be corrupted by bad actors. What happens when your religious leaders, who you trust as interpreters of God’s word, ask you to do things you think are bad?

One thousand years ago, Pope Urban II asked his followers to undergo the First Crusade to take back Jerusalem from Muslim control. Countless Muslims and Jews were slaughtered by the Christians. The slaughtering of these people seems to kind of go directly against the Sixth Commandment, which states pretty clearly: Thou shalt not murder.

So how did Pope Urban II and the following popes over the following 200 years’ worth of crusades justify the murdering of all these people? Well, silly peasant, these crusades were sanctioned by God himself as a part of a holy war. Killings during a holy war are acts of faith, not sin. The Pope, I think, speaks directly to God and gets the inside scoop on what He wants. When he wants you to kill people in a city because Christians are supposed to live there because God wants them to live there, you go kill people in that city.

A power play for more land in a highly sought after part of the Middle East? Clear incentives for the Pope to make up a justification for a war that will bring him both more power and more wealth? YOU BIGOT. HOW DARE YOU ACCUSE THE POPE OF SUCH IMMORALITY. Now, go kill people who believe in a religion that’s vaguely similar to your own because, supposedly, it’s somehow inferior to your own. God asked you nicely, after all.

Now, you don’t have to tell me twice that the crusades were clearly immoral by today’s standards. I would humbly argue that my morality reigns supreme over the popes’ who carried out the crusades. I’ve never killed a Jew for living in a city that I thought they didn’t belong. I actually never even had the thought that any Jew shouldn’t be in any particular city. I really don’t mind. Come to think of it, I’ve never slaughtered anyone. Not even a single person! But somehow, even with all these commandments that tell Christians in plain English (well, kinda plain English) not to do these things, their leaders can still convince them to carry out these horrific acts. Strange.

Not only do these religious leaders sometimes ask you to do things that are clearly against the word in the Bible, but it also seems that the Bible (and the leaders who preach it) uses morality as a fear tactic to get people to believe in God. If you’re a sinner by living in contrast to God’s will, you can acknowledge and repent for your sins before God and be forgiven for them. No matter the severity of the sin. From stealing a pencil from your older sister to murder, you can still gain access to Heaven if you’ve followed the steps to forgiveness. But as an atheist, I’m constantly living in sin for not having faith in Jesus Christ. That means, even if I give my sister her pencil back and never murder a person (as, historically, I have not), I don’t get to go to Heaven.

After going to church with one of my clients, I asked her about this inconsistency (or so it seems to me). Her counterargument was that, according to God, all sin is created equal. God is so perfect, and he is so far above a normal person that he has a hard time distinguishing between the severity of any sin. So, that means, a man who raped and murdered a college student out on a jog and me (for not accepting Jesus as my savior because I don’t think there is evidence for his existence) are one in the same (as far as our sins go, at least, I guess(?)).

However, if the murder-rapist guy repents for his sins and asks for forgiveness, he gets access to the pearly gates. He just really has to mean it when he repents. Meanwhile, if I keep being an atheist, even if I murder-rape exactly zero people, I burn in Hell forever.

?

The morality of religion is so dogmatic that it often seems broken. Or just breaks its own rules entirely. It doesn’t feel right to me that a religious leader can convince their followers to conduct completely disgusting acts because they decided to interpret their religious text in a certain way. And it doesn’t feel right to me that God wouldn’t accept me into Heaven for questioning His existence, when he didn’t come to be once in a clear way to demonstrate it. But, the dude who murder-raped Sarah from biology class gets a place in eternal paradise.

I know I’ve bashed a lot on the Bible. But other religions are just as bad about using their holy texts for bad instead of good.

We used to have these beautiful identical towers in Manhattan that stood taller than any others in the world before Muslim extremists crashed planes into them, killing thousands of people in the process. These Muslim extremists were convinced by their religious leaders that their sacrifice would grant them seventy-two virgins in paradise.

But the Qur’an doesn’t even say this. It says something vaguely similar that believers will be granted access to paradise with companions of purity. Which sounds a lot like the Christian idea that accepting Jesus grants you access to Heaven. But the religious leaders of these Muslim extremists take it thirty steps too far. For their followers, “believing” is now “sacrificing” and “companions of purity” is now “72 virgin women with whom you get your way with”. And although people may think “72” is a random number of virgins, I think it’s actually a clever psychological tactic that these leaders are using to convince their followers that it’s real. Good negotiators use a similar tactic when trying to mitigate haggling over the price of something. Specificity makes something feel more real. It appears to me that these religious leaders can be good manipulators.

How are these religious leaders able to take such liberty with the supposed work of God? The answer: fiction. Morality derived from religion is flawed because it’s based upon fictitious texts. And clever manipulators can take these works of fiction and interpret them however they want to get their followers to bend to their will. And I’ll be even more harsh here. I’ve hardly met a single Christian who has read the entirety of the Bible. I’m surrounded by Christians here in Naples, Florida. They do Bible study weekly and go to Church every Sunday, but when I asked many of them recently about the story of Jesus and the fig tree, they had never heard of it. Some of the people I asked even denied its existence in the Bible until they investigated it and realized I was right. This story, a confusing one where Jesus kills a tree because he is hungry, is really in the Bible. Of course, they came up with their own interpretations on how this story actually shows Jesus being perfect, not flawed like the rest of us. They said he is teaching me an important lesson in not being fruitless. But I didn’t buy it.

If these people aren’t even reading the book that all their truth comes from, how can they determine what is true at all? And how can they argue with their pastor when he tells them to do something that seems wrong, especially when that pastor tells them that the command is actually coming from a passage they have never read before? Or even worse, how can they tell their pastor they are wrong, when all fiction can be interpreted in different ways by different readers?

My overall argument is that religion is not the best way to get your morality. It’s probably the best way humans have now. But, in my opinion, that isn’t saying much. We need a new framework upon which to create our moral compass. One that provides a more consistent and universal approach to dealing with our fellow humans.

If not religion, then where should I get my morality?

I said that certain things like killing Jews and Muslims for living in a particular city or flying planes into buildings in the pursuit of virgins in paradise are immoral. Many would agree. Some will disagree though. And that’s the problem. We have no universal meaning of morality. Just look at Merriam-Webster’s definition of morality. It’s a list of possible definitions. Here’s all of them:

a. a moral discourse, statement, or lesson

b. a literary or other imaginative work teaching a moral lesson

c. a doctrine or system of moral conduct

d. particular moral principles or rules of conduct

e. conformity to ideals of right human conduct

f. moral conduct : virtue

One of the key features of a bad definition is that the word, or a derivative of the word, is used in the definition. All these definitions, except for ‘e’, have the word ‘moral’ in them. Based on these definitions, how is anyone supposed to know what is a moral action and what isn’t? And when one religion tells me that I’m allowed to stone my wife if she commits an act of adultery and another tells me that I’m absolutely not allowed to stone my wife if she fucks Greg, how am I supposed to determine which religion is best for me? Both options seem enticing. If I want to be objective about morality, how am I to choose?

I, for one, think morality should be tied to one specific outcome. And that outcome is determined by asking yourself this one question:

If I commit this act, is it likely to improve humanity in the long term?

Each part of this question is carefully thought out. And revised many times using ChatGPT.

I chose “If I commit this act” because only you have control over what you do. Morality is personal. Religions will try to convince you that it is cultural. But ask any Christian how they feel about gay marriage. In edge cases such as this, they will have completely different answers. Some think it’s fine. Some think it’s a sin and shouldn’t be allowed in the church but are happy to allow gay people in their church. Some will not accept gay people in their church.

What about capital punishment? Many people of any faith are totally okay with capital punishment. You kill a member of society, society kills you. Simple.

But what about the Sixth Commandment? I’m pretty sure it says “Thou shalt not murder,” not “Thou shalt not murder unless the murderee was previously a murderer.”

These examples prove that today’s morality is subjective. Each person has their own view of morality. Even people of the same religion have their own view of morality. Clearly, our current moral frameworks are failing us. I want this new and simple framework to take out as much of the subjectivity as possible.

The second piece, which is calling for the improvement of humanity, is also crucial. If you’re determining the morality of your actions by what benefits you, you’ll be able to justify the morality of a lot of harmful shit.

Are you hungry? Just steal some food from a gas station. It’s easy to not get caught. And if you’re living in modern San Francisco, getting caught won’t even lead to repercussions if you keep your theft under a certain dollar amount. This benefits you greatly. You solve your hunger problem with zero cost to you.

Are you mad at UnitedHealth for malpractice in the health insurance industry? Go kill the CEO so you can become famous as a martyr and gain the sexual arousal of countless women for your deed. You get fame and pussy. Congrats, Luigi.

Also note that in the second part I wrote “likely”. Because let’s be honest, we can never be absolutely sure of the chain of events resulting from our actions. We must act. And cannot be paralyzed by fear. Our goal is to try to do the right thing. Even if sometimes we fail.

But we will fail less if we deeply consider the third part of this self-referential question. This part of the question implies that the long-term outcomes of your actions are important. Not just what happens tomorrow. But what happens for years and decades and centuries to come.

Let’s go back to the psycho-females new love interest, Luigi Mangione. Be him for a moment.

You want to benefit humanity, and you decide to kill the CEO of UnitedHealth. Sure, it might arouse some conversation to the faults in the health insurance and healthcare industries. But you’ve now created an environment where CEOs can be targets of assassination, destabilized the family of the father that you killed, and probably not lead to the implementation of any policies that provide clear restrictions of how health insurance companies should behave to benefit humanity. Also, you didn’t fix the real problem, which is most likely the bureaucracy in the healthcare system (you also admitted that you didn’t understand the problem and decided to kill anyway, fucking idiot). Time will tell, but long-term I’m pretty sure that the death of Brian Thompson is going to be long-term bad for humanity.

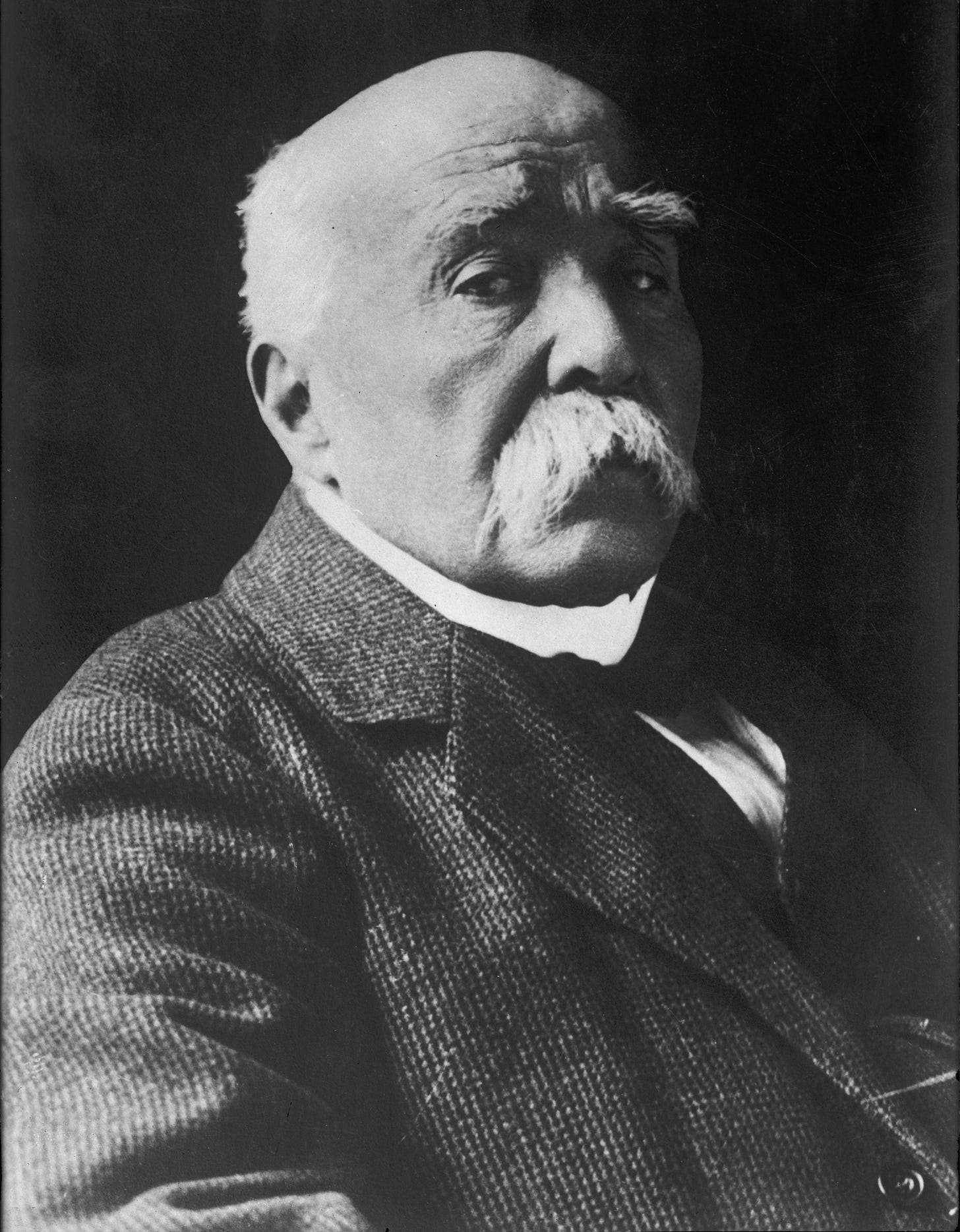

We can also ask the same questions about decisions that happened in the distant past. Take yourself back to WWI. Put yourself in the shoes of Georges Clemenceau, the then Prime Minister of France.

You want to end a war that is killing millions of men in horrific trench warfare, so you draft a treaty that imposes guilt and reparations upon Germany. Sure, you might have stopped the death of a few million more people over the next couple of years, but you also laid the foundation for almost a hundred million more people to die just a few decades later. The Treaty of Versailles might have solved a short-term problem for humanity. But it created devastation in the long-term. It might not have been the only thing that caused WWII, but destabilizing Germany was surely a major contribution.

Let’s take these three examples I gave (stealing from a gas station, the killing of Brian Thompson, and the Treaty of Versailles), and change the decision making by applying the framework I provided in the central question I believe the thief, Luigi Mangione, and the authors of the Treaty of Versailles should have asked themselves before carrying out their actions.

If these people were to ask themselves - If I commit this act, is it likely to improve humanity in the long term? - what would they have done instead?

The thief might have decided to just pay for the sandwiches he was thinking about stuffing into his hoodie pocket and running off with. He still gets to eat. And the shop owner gets to keep operating his business at a profit, allowing the people who come to the gas station behind him many more years of having a convenient way to get food, coffee, and gas. And, when he comes back a few days later to get more sandwiches, he can be sure that the store will still be there to provide him with more sandwiches.

The thief should have chosen not to steal. Morality case one closed.

Luigi Mangione might have decided not to kill Brian Thompson. Instead, he would have used his connections inherited from his family and built through years at an Ivy-League university to build a career as a lawyer or in politics. He could have helped defend those wronged by health insurance companies. Or he could have passed legislation that changes the way healthcare companies and health insurance companies conduct business with one another, reforming the system which is inherently broken. A career in law or politics could help create an industry dynamic in healthcare that change the lives of millions for the better for decades to come.

Luigi Mangione should have chosen not to murder. Morality case two closed.

The authors of the Treaty of Versailles might have chosen to forgive Germany for being the aggressors in World War 1. They would not have forced them to pay reparations which bankrupted Germany and created currency hyperinflation. They wouldn’t have drafted the War Guilt Clause, which demoralized Germany and made them hate, well, the entire world. Both features of the Treaty, which if avoided, could have stopped the rise of radical Hitler, who became the voice of the downtrodden German people.

The authors should have chosen forgiveness. Morality case three closed.

I could come up with case studies all day using this framework. And I could defend decisions and reevaluate others to come up with better decisions. And do you know what my decisions would end up looking very similar to? I’ll give you a hint.

“Thou shalt not steal,” is the Eight Commandment.

“Thou shalt not murder,” is the Sixth Commandment.

Matthew 6:12 reads:

“And forgive us our debts,

as we forgive our debtors.”

These ideas: don’t steal, don’t murder, and forgive others, are shared across religions. So are many of the other morality frameworks of Christianity.

Religion is incredible in that these old texts and ancient traditions give people an incredible framework to do good. And their similarities show that humans, intrinsically, have a moral standard that encourages the success of the species in the long-term.

But my problem comes back to the 72 virgins and the crusades and the fiction. When there is fiction at the root of morality, interpretations can be made. And when there’s faith in something without evidence, dogmatism will reign supreme.

If we want a consistent and actionable moral compass that causes people to act for the benefit of humanity in the long-term, we need objectivity. And where will we find this source of objectivity?

History is Our Moral Guide for the Future

In my blog on why you shouldn’t believe in Heaven, I discuss Bayesian reasoning. Briefly put, Bayesian reasoning suggests that when you make a decision but are subsequently provided with new information on your situation, you should most likely adjust your decision to match the suggestions of the new data. Now, Bayesian reasoning is not a good way to create new knowledge, as some may think. But it is a great way to guide your decision making on morality.

The problem with Bayesian reasoning is that when you run into an edge case that has no historical precedent, you cannot use it as a decision-making mechanism. But, for almost all moral dilemmas, we have enough historical precedent to guide us. We know this. Because most religious texts were written thousands of years ago. And despite this, they still are able to provide us with moral guidelines that most people would agree with. Now, with thousands more years of experience and way better ways of confirming the validity of a story, we can use these historical stories, like the drafting of the Treaty of Versailles, to tell us how a treaty after a similar set of circumstances should be drafted in the future to prevent a potential world war.

Should I assassinate this CEO? Well, previous assassinations have led to deeper political and societal divides, increased security measures (which drove up cost and friction of being in positions of leadership), decreased the incentives for smart people to take positions of leadership due to the fear of assassination, and lead to the families of those who were assassinated to be destabilized. Probably not worth the upside of awareness of a particular issue. Especially when awareness can be built in far more peaceful ways.

How can we use Bayesian reasoning and history to resolve the Ukraine War? You might disagree (and it’s maybe slightly more complex), but the Ukraine War began by the US backing Putin into a corner by intimating the expansion of NATO into Ukraine. This is something Putin argued was a red line and would result in an invasion of Ukraine. Biden doubled down on his commitment when he became President. Russia invaded Ukraine. What a fucking surprise.

But look at the resolution of the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. The Soviet Union placed nuclear missile bases in Cuba. Cuba, is, like, really close to the US. This was seen by the US Warhawks as an act of war provocation (because it was). President Kennedy’s cabinet wanted him to invade Cuba and go to war with the Soviet Union. But Kennedy wanted to avoid war (thank God, no pun intended). So, he created a direct line of communication with Soviet Union Premier Nikita Khrushchev. They solved the problem diplomatically. Publicly, the Soviet Union removed their nuclear missiles from Cuba. Privately, the US removed their nuclear missiles from Turkey. Potential war avoided.

Okay, so what could we have done (and can still do) for the Ukraine War to prevent it or stop it from continuing. Preventing it would have meant that we do not expand NATO to Ukraine. This seems simple. NATO is adversarial to Russia. Ukraine is a Russian border country. Seems like a fair deal. As a trade-off, a deal could have been struck to restrict Russia’s ability to invade Ukraine. You can imagine a million ways to do this, but whatever way you come up with would have probably stopped the war in Ukraine from happening.

How about now? How could you stop the War from continuing? One way would be to double down on the US war efforts in Ukraine. Beat the Russians with our more advanced technology and skilled military personnel. Sign a treaty that ends the war, blames Russia for the conflict, and makes them pay reparations to Ukraine for the destruction caused in Ukraine. Bankrupt Russia, cause hyperinflation of their currency, and demoralize one of the most powerful countries in the world.

This would work… for a short period of time. The war would end. And over the next five to ten years hundreds of thousands to millions of lives would be saved. But I’m pretty sure I don’t need to tell you what would happen ten to twenty years later.

If this was your choice, you are committing an action that would likely improve humanity in the short term.

The other solution would be to solve it diplomatically. Pull American weapons systems out of Ukraine, rescind the permission of the use of long-range missile systems provided by the Biden Administration in his final hours as president. Restrict Ukraine from becoming a NATO ally. And secretly sign a deal with Russia to remove nuclear weapons from some location that they probably have set up recently near the US border (I’m guessing, by the way). Don’t make Russia pay reparations. But allow the US and NATO countries to provide funding to Ukraine to rebuild its destroyed cities.

Give the Russians a golden bridge to retreat across. Sun Tzu would approve, I think.

If this was your choice, you are committing an action that would likely improve humanity in the long term. You have a good sense of morality, in my humble opinion.

But using this framework isn’t enough. You must incentivize people to want to do it. And to do that, you need Skin in the Game…

Part 3 Coming Soon

Read Next: Why You Shouldn’t Believe in Heaven

Wait, Don’t Go!

Dear reader, I know there is only a few of you. And I see you all. Substack gets me all the juicy data on who is reading these things. And I deeply appreciate you for being here.

Before you go, could I ask you a favor? If you could please drop a ‘Like’ by clicking the heart button, that would be amazing. It would only take you less than a second.

Also, I want to chat with you and hear your opinions! The best way to get me to answer any questions you have is by using the comment section. Drop a comment and I’ll make sure to reply!

And if you have any friends who might like this piece, please give it a share! Show your friends how smart you are by proving to them that you still know how to read.